by Brian Lazar

Despite more modest snowfall than we saw across the state in December, we ended the first month of 2020 with the Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) over 100% of the long-term median across all of Colorado’s river basins. January had light and fairly continuous snowfall, characterized by several small to mid-size storms and interspersed with short dry spells. Crusts and weak layers formed in the upper snowpack during these dry spells. Each loading event of more than a few inches of snow spurred some avalanche activity. The month also saw several very strong wind events which dramatically altered the alpine landscape and redistributed snow in many areas.

The CAIC recorded 648 avalanches in December. One hundred and twenty nine of those avalanches were human triggered. Twenty-three people were caught in avalanches during the month, including 11 people in one week between January 18 and January 25. Five people were partially buried, 3 were injured, and tragically, one person lost their life when they were hit with a mix of falling ice and snow. This was the second avalanche fatality in Colorado of the 2019-2020 season.

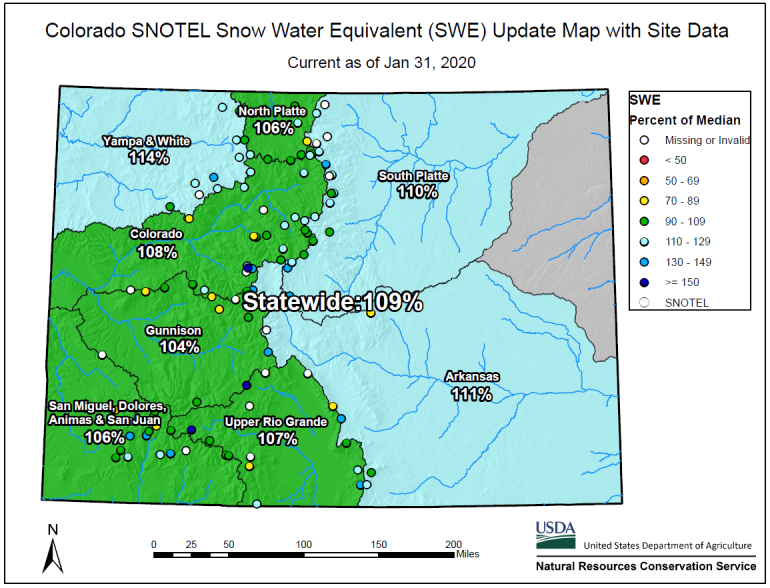

This figure shows the basin-wide percent of normal (percent of median from 1981 to 2010) snow water equivalent (SWE) across Colorado at the end of January.

The first storm of the month dropped 8 to 12 inches of snow from January 2 to January 4. This led to our first avalanche cycle of the month, including our first avalanche involvements. Avalanche incidents during this period were concentrated in the Northern Mountains. A skier triggered and took a short ride in a small avalanche on Loveland Pass on January 2. A similar incident occurred in Rocky Mountain National Park on January 5. Also on January 5, a skier triggered a small avalanche on Coon Hill on the west side of the Eisenhower Tunnel and was carried several hundred feet before coming to rest. A few days after the storm ended a CAIC forecaster triggered and took a short ride on the south side of Coon Hill as well. Fortunately, no one was buried or injured in these incidents.

A skier-triggered avalanche on Coon Hill west of the Eisenhower Tunnel on January 5. The skier was carried several hundred feet through the rock chock, but was not buried nor injured.

We had a four to five day dry spell after Jan 5, along with very cold temperatures. This formed a very weak layer of near-surface facets in most mountain locations. This near-surface weak layer showed its potential to produce avalanches when the second notable storm system arrived in the second week of January. This storm dropped between 4 to 8 inches of snow in most mountain areas between the 10th and the 14th, with snow coming earlier in the San Juan Mountains and later in the Central and Northern Mountains. This modest loading event led to a fairly widespread avalanche cycle.

There were 35 reported avalanches in the Northern Mountains. Eleven of those avalanches were large enough to injure a person. Most avalanche activity occurred on north to east to south-facing slopes. We received reports of one partial burial near the Eiseman Hut on January 10. There were no other avalanche involvements during this second storm.

Skier-triggered avalanche near the Eiseman Hut on January 10, 2020. The skier was caught, carried and partially buried, but was not injured.

The CAIC recorded 49 avalanches during this time period in the Central Mountains, 31 of these avalanches were large enough to injure or kill a person. The CAIC also recorded 29 avalanches in the Southern Mountains all of which were large enough to kill or injure a rider. Similar to the Northern Mountains, most avalanches in the Central and Southern Mountains occurred on northwest to east to south facing slopes.

Large natural avalanche on a southeast aspect of the Clark Peak bowl above Jewel Lake near Cameron Pass. January 14, 2020.

We had another dry spell from January 15 to 18, when our third notable storm system arrived. It wasn’t a big system to start, dropping only around 6 inches of snow in most mountain areas by January 19, but this was quickly followed by a bigger system on January 22 and 23, which added another 7 to 14 inches of snow. This one-two punch kicked off our most concentrated week of avalanche incidents during the 2019-2020 season.

The Steamboat area, which had seen little activity outside of small storm-snow avalanches up to this point, reported its first large skier-triggered Persistent Slab avalanche on January 19, breaking 3 feet deep on the January 9 layer. Between January 19 and 25, 8 people were caught and carried in avalanches in the Northern Mountains. Two partially buried. One of these was a climber in Rocky Mountain National Park who triggered an avalanche and was washed over a 50 foot cliff. Fortunately, this resulted in only minor injuries. A backcountry skier was also seriously injured after being caught and carried in a large avalanche near Jones Pass on January 22.

This is an image of the Dragon Tail Spire taken on Jan 16, 2020, three days before the accident. The red circle marks the approximate area where a climber triggered the avalanche. The red line shows where he was carried down slope, and the yellow line shows the approximately trajectory of his free fall after being washed over the cliff edge.

Looking at the crown face of a larger avalanche that caught, carried, and seriously injured a skier near Jones Pass on January 24, 2020.

In this same week a skier was caught and carried in an avalanche in Red Lady Bowl above Crested Butte. In the Southern Mountains an ice climber was killed in the Uncompahgre Gorge on January 18 after an ice pillar broke loose, entrained small amounts of loose snow, and hit a climber with chunks of ice and snow, burying here in the creek below. This was the second avalanche-related fatality in Colorado of the 2019-2020 season. The week closed out in the Southern Mountains with a snowmobile triggered avalanche near Molas Pass that caught and carried a rider.

An aerial image of the upper portion of The Dungeon ice climb on January 20, 2020, two days after the accident. A large chunk of ice broke away from the hanging pillar and triggered a small loose snow avalanche on the rock slab below.

After January 25, Colorado saw another brief dry spell before our fourth and final modest storm system arrived on January 27. Once again the storm differed slightly in timing but was egalitarian in delivering around 7 to 14 inches of snow to most mountain areas through January 28. This kicked off yet another avalanche cycle and another round of avalanche incidents.

The CAIC documented 21 avalanches in the Northern Mountains during or immediately after the fourth storm. Nine of these avalanches were large enough to kill or injure a person. All of these avalanches occurred in the Vail-Summit and Front Range zones. Two people were caught in avalanches including an on duty patroller. There were 14 avalanches in the Central Mountains, 3 were large enough to kill or injure a person. A snowmobiler was caught and partially buried on January 20 near Kebler Pass west of Crested Butte. The CAIC received reports of 23 avalanches in the Southern Mountains. Thirteen were large enough to kill or injure a skier. Three people were caught in avalanches in two separate incidents in the South San Juan Zone.

Small skier-triggered Wind Slab avalanche on a north aspect above treeline that caught two skiers. North Twilight Peak, South San Juan. January 31, 2020.

We closed out January with only a few avalanches breaking near the ground. Most avalanches released in storm or wind-drifted snow, or on weak layers buried in the middle of the snowpack. Basal weak layers remained a concern in our thinner snowpack areas, but it was going to take larger loading events to see deep avalanches.