Ethan Greene and Spencer Logan

News reports and social media threads about avalanche accidents often include some discussion of people’s experience level. The people involved in the accident are commonly described as “expert skiers” or “experienced snowmobilers”, but the single label can conflate someone’s riding skills and avalanche experience. Peers sometimes proclaim the group displayed a significant lack of experience, understanding of avalanche phenomena, or implementation of common safety practices. Occasionally someone presents the argument that only people with avalanche experience and training are caught in avalanches. We decided to dig a little deeper into the avalanche accidents in the 2019-2020 season, and take a closer look at the avalanche education and experience levels of people involved in these events. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic also provided an opportunity to look at accidents before and after the shutdown in the spring of 2020.

Avalanche Accident Tracking in Colorado

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) has been documenting avalanche accidents in Colorado for decades. Over the years the effort has expanded from fatal accidents to include all avalanche involvements. Basically, we try to collect some information any time someone is caught, carried, or buried in an avalanche. We learn about these events from reports sent to us by the public, connections with county sheriff’s offices or search and rescue groups, media articles, threads we see on social media, talking to people at the grocery store or post office, and sometimes just rumors we hear from our friends and families. We typically reach out to the people involved, try to verify some details, and gather whatever additional information we can. When someone is killed in an avalanche we conduct a more detailed investigation and interview as many witnesses and survivors as possible. You can read those reports here and see a summary of what we’ve collected over the last 20 years in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Number of reports to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center of people caught and killed in avalanches during the last twenty Colorado avalanche seasons.

What We Did

Other researchers have examined the education and experience levels of people involved in avalanches, but they focused on the victim’s avalanche training and self-assessed avalanche experience (McCammon 2000, Zweifel et al. 2012, Martensson et al. 2013). Because we don’t interview everyone involved in every accident, we don’t know all the avalanche classes taken by all the people in the group or their self-assessed avalanche skills. As such, we developed alternative tools to categorize a person’s avalanche experience.

For avalanche education level, we created the Avalanche Education Level (AEL) scale (Table 1), based on the American Avalanche Association’s course progression. The AEL just looks at if someone either has or has not reported taking an avalanche class at a particular level.

Table 1. The Avalanche Education Level (AEL) scale we used to categorize people’s education levels and brief descriptions of the courses.

| AEL (codes used in other tables and graphs) | Reported Education |

| Unknown (Unk) | Unable to categorize |

| None | No formal avalanche training |

| Awareness (Aware) | Awareness or introductory avalanche education |

| Level 1 (Lev 1) | Three-day course including instruction in classroom and field |

| Level 2 (Lev 2) | Advanced training for recreationalists |

| Professional (Pro) | Professional-level courses with structured evaluation |

We also developed the Inferred Avalanche Experience Level (IAEL) scale (Table 2) to rank avalanche experience from indirect evidence like an observation report, interviews, or descriptions from other people. We based the IAEL on the National Institutes of Health’s Competencies Proficiency Scale (CPS). The CPS is a human-resources tool that allows interviewers to rank a candidates’ experience. It is also used as a self-assessment to see where your experience places you in your career progression. The CPS has parallels with the Dreyfuss Learning Model (Dreyfuss and Dreyfuss 1980) that allows researchers to assess how well people learned a set of skills or knowledge through training and instruction. Researchers in Canada (St Clair 2019) used similar models to assess avalanche forecast users. You may have taken their survey a few years ago, or seen one of their presentations at an annual Colorado Snow and Avalanche Workshops (CSAW). None of the previous models were directly applicable to what we tried to do, but did allow us to develop a scale that relates to other assessment efforts. At each level, we developed examples of evidence to help us infer experience. We used evidence like statements from the group, their use of technical language in an observation, descriptions of pre-trip planning, and if they used safe travel practices. The IAEL is a subjective scale, but one that is relatively repeatable between researchers.

Table 2. The Inferred Avalanche Experience Level (IAEL) scale and some of the guidance we used to categorize people’s experience.

| IAEL (Codes used in other tables and graphs) | Guidance |

| Unknown (Unk) |

|

| None |

|

| Beginner (Begin) |

|

| Intermediate (Int) |

|

| Advanced (Adv) |

|

| Expert (Exp) |

|

| Authority (Auth) |

|

We used the definitions in Snow, Weather, and Avalanches: Observation Guidelines for Avalanche Programs in the United States (American Avalanche Association, 2016) to define the types of avalanche involvements and select events for the dataset. We identified as many people as possible involved in these avalanche incidents. If there were five people in a party, but only one person caught, we determined individual IAEL values for each of the five people. While imperfect, this allowed us to include people who were not caught in the avalanche, but participated in the event and decisions made by the group.

We applied the AEL and IAEL scales to all the people we identified. We used all information the CAIC gathered, from detailed interviews and accident reports to brief observations submitted by the public. Some involvements were reported second-hand, with no information directly from the parties involved. The AEL and IAEL scales allowed us to assign levels to people when there were different amounts or different types of data available.

We used the Tier 1 avalanche danger rating to examine avalanche danger relevant to avalanche incidents. The Tier 1 rating is the highest avalanche danger level issued for a specific place and time. It’s displayed on maps of avalanche danger and used as the overall danger for a forecast region. The CAIC issues forecasts with different spatial extents depending on the time of year, and the Tier 1 rating allows for consistent comparisons between different days in the forecast season.

Significant impacts of the global COVID-19 pandemic began in Colorado in mid-March 2020. To examine potential changes in patterns of avalanche involvement, we chose 13 March 2020 as the pre- and post-pandemic division. On or around that date, cities and counties began imposing a patchwork of travel restrictions and public health rules. The State of Colorado closed ski areas and other public venues to reduce the virus transmission. CAIC staff and other professionals noted a significant increase in backcountry use following the closures.

What We Found

The CAIC documented 86 avalanche incidents during the 2019-20 season, and we identified 126 people involved in those incidents. There were 88 people caught and carried in moving avalanches, including six people fully buried and six people killed. There were eight people who triggered avalanches but were not caught, and 30 people not touched by moving debris. We identified gender for 76 people, 63 males and 13 females. There were 86 human-powered backcountry tourers, 13 motorized users, and a handful of hikers and climbers, as well as other activities.

We categorized all 126 people with the AEL and IAEL (Table 2). We were able to assign an AEL to 31 people. Of those, 29% appeared to have no formal avalanche education and 29% had taken a Level 1 avalanche class. Of the people who had taken a Level 1 avalanche class, five of them were involved in two separate incidents that resulted in avalanche fatalities. That may indicate a selection bias. CAIC investigators try to collect avalanche education levels when investigating fatal avalanches. Education levels were much less frequently available when people self-report avalanche involvements.

We assigned IAEL to 89 people. Fifteen percent of people were categorized as beginners, 25% intermediate, and 47% advanced. We saw the expected correlation with AEL and IAEL (Table 3)–the more experienced a person was with avalanches, the more formal education they tended to have. There were four people with advanced experience that had not taken formal avalanche classes, a reminder that education is important but not the only way to gain knowledge. Likewise, we found a range of inferred avalanche experience for people who had taken a Level 1 avalanche class. Education is important but not a substitute for applied experience.

Table 3. Counts of IAEL (horizontal) and AEL (vertical).

| Unk | None | Begin | Int | Adv | Exp | Auth | Totals | |

| Unk | 37 | 10 | 18 | 28 | 2 | 95 | ||

| None | 3 | 2 | 4 | 9 | ||||

| Aware | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Lev 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 | ||||

| Lev 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Pro | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | ||||

| Totals | 37 | 3 | 13 | 22 | 42 | 7 | 2 | 126 |

Most people involved in avalanches had intermediate or advanced levels of experience, which is consistent with previous research (McCammon 2000, Tase 2004). McCammon (2002) found that avalanche education did not reduce avalanche exposure. Instead, our results suggest people were using their training and experience to spend more time traveling in avalanche terrain, or traveling during more avalanche-prone conditions.

The distribution of AEL differed significantly (p<0.05) prior to and post pandemic-related closures. The proportion of people that completed a Level 1 avalanche class and were involved in an incident increased after the pandemic closures. On the other end of the education spectrum, we identified eight professionals involved in avalanches in the 2019-20 season, five who were caught. All five of the professionals caught occurred in avalanches prior to the pandemic closures, and three were ski patrollers caught in avalanches during early season avalanche mitigation. Only one professional was involved in an avalanche incident post pandemic closures, and they were not working when the incident occurred.

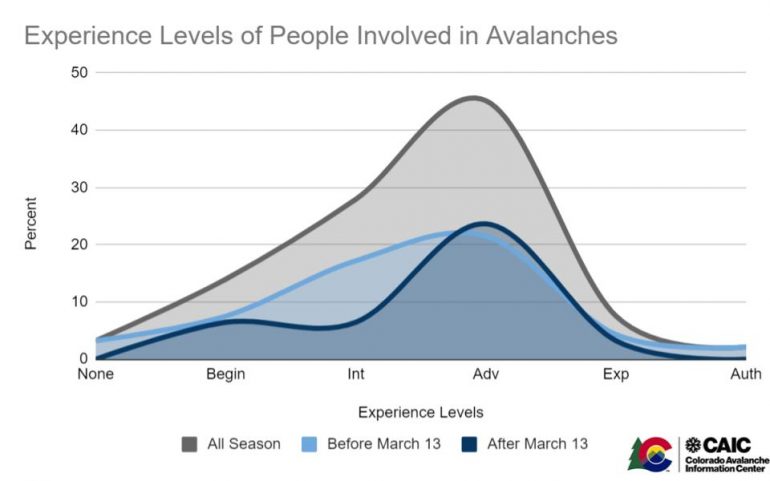

Likewise, there was a significant (p<0.01) change in the IAEL of people involved in avalanches before and after the pandemic-related closures (Figure 2), with the proportion of people involved shifting towards Advanced backcountry travelers after March 13. The proportion of Beginner backcountry travelers did not increase after March 13. We don’t know why this occurred, but there’s some anecdotal evidence that may help explain the shift. As recreation increased after pandemic closures of ski areas and other activities, easily-accessible areas became crowded and tracked up. More skilled recreators used those skills to push into less-familiar terrain or explore new areas. Like McCammon (2004) showed, they were using their skills while accepting an increased avalanche exposure. Some observers reported an “increase in risky behavior” or people “taking more avalanche risks.” These are very subjective observations, but consistent with research on increased risk acceptance in stressful situations (See Sapolsky 2017 for a summary). The uncertainty of a global pandemic is certainly a stressful situation.

Figure 2. Inferred experience levels, by percent, for people involved in avalanches in 2019-2020 avalanche season. The gray curve shows experience levels for the entire season. The light blue and dark blue curves show experience levels pre- and post- pandemic related ski area closures around March 13. The shift to more experienced people involved in avalanches after March 13 is statistically significant.

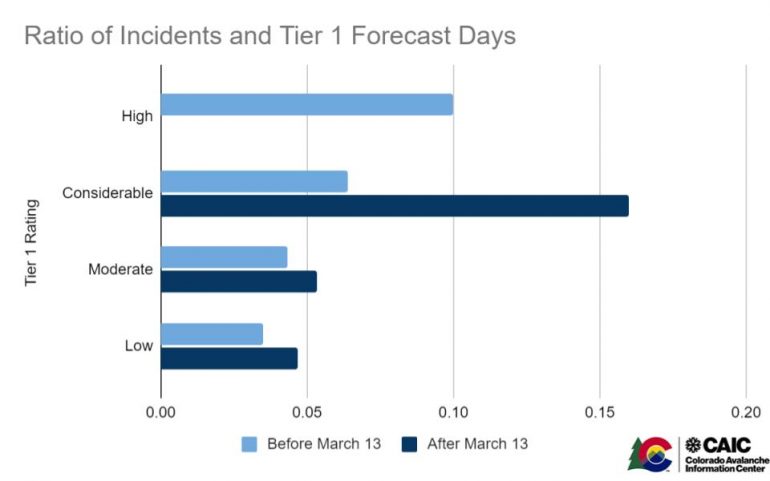

In Colorado, most avalanche accidents occur when the avalanche danger rating is either Moderate (Level 2) or Considerable (Level 3) (Logan and Greene 2018). This was also true during the 2019-2020 avalanche season with 60% of the incidents occurring at Moderate (Level 2) and 30% at Considerable (Level 3). An important point is that the CAIC issued a Moderate (Level 2) rating for 68% of forecast days in 2019-20. For a better comparison of incidents and danger ratings we looked at the ratio of the number of incidents at a Tier 1 danger rating to the total number of days with that Tier 1 danger rating (Figure 3).The number of incidents that occur at a Considerable (Level 3) danger rating is disproportionately large relative to the number of days that danger rating is issued. The proportion of avalanche incidents at Considerable (Level 3) danger to the total days with that danger rating is even more notable when considering the pre- and post pandemic periods. While half of the incidents at Considerable (Level 3) occurred before the pandemic related closures, the other half occurred after the pandemic shutdown even though only 17% of the forecasts between March 14 and May 31 had a Tier 1 danger rating of Considerable (Level 3). The comparative ratios are 0.06 before, and 0.16 in the post-pandemic period. The ratio for incidents at Considerable (Level 3) post-pandemic indicates a very high rate of incidents on days with relatively dangerous avalanche conditions. Like the shift we observed in IAEL, the number of incidents at Considerable (Level 3) after March 13 suggests that backcountry travelers were accepting greater avalanche exposure during hazardous periods.

Figure 3: The ratio of the number of incidents at a Tier 1 avalanche danger rating compared to the number of forecast days with the Tier 1 avalanche danger rating during the 2019-2020 avalanche season. The light blue and dark blue bars show the ratios pre- and post- pandemic related ski area closures around March 13. The Tier 1 rating is the highest single rating for any area issues for a 24 hour period.

Why Should We Care?

These results add to the ongoing discussion about education, experience, and avalanche accidents. Our approach provides a novel way to look at the experience level of people involved in avalanches, but there are also some limitations to keep in mind. First, our dataset is relatively small, consisting of a single season in Colorado and just the avalanche involvements reported to the CAIC. Second, our dataset is biased, as it only includes people involved in avalanches. The people who successfully avoid avalanches, with and without formal training and years of experience, are not included. Despite these limitations, this work provides an opportunity for all of us to think about who is getting involved in avalanches, how each of us might fit in that group, and hopefully how we can avoid a serious accident.

Nearly 40% of the people caught in an avalanche or in a group with someone caught in an avalanche, had taken a Level 1 avalanche class. According to our IAEL, about 70% had intermediate or advanced avalanche experience. This begs the question: Does formal, field-based training or avalanche experience increase or decrease your chance of getting caught in an avalanche? This study cannot answer that question. People that invest in avalanche education and gain experience in the mountains typically do so because they spend time in avalanche terrain, which increases their exposure to avalanches. In aggregate, the additional exposure may offset the application of risk-reduction strategies. Merging the benefits of careful terrain choices and snowpack analysis with the increasing exposure as the number of days in the field climbs is a challenging problem. We will leave those analyses to a talented and well-funded research group, but we are eager to hear what they find out.

Last spring the impacts of COVID-19 produced a dramatic increase in backcountry recreation. Based on the increased use of public lands over the summer, and the increases in sales of winter backcountry equipment, the upcoming winter promises more of the same. Our comparison of pre- and post-COVID periods suggests we may not see an increase in avalanche accidents driven solely by a flood of new users. Clearly the conditions that lead to an increase in avalanche accidents involve the interaction of multiple factors: more people in avalanche terrain, more use in easily accessible areas, more people moving into new areas looking for solitude or fresh snow, changes in the distribution of education and experience, and a myriad of other factors.

What should we do?

This project suggests we should all take a hard look at the assumptions we make about ourselves and our riding partners. Are we using our experience and skill to make good decisions, or are we just lucky? Are we correctly identifying avalanche hazards, the terrain where they exist, and making choices to reduce our risk? Or are our decisions based on experience built by a series of positive-feedback events and emotions driven by our pleasure-seeking brains. One strategy is to read and discuss accounts of avalanche accidents. To get the most benefit we need to think about what those people were experiencing as well as similar situations we have faced. A common tendency is to look for reasons why we would have done something different or why our education or experience would have produced a different result. This tendency, known as the blind-sight bias (Pronin 2008), can limit our ability to avoid a similar outcome when faced with similar circumstances.

We started this project to help us understand how people are interacting with avalanches in Colorado, and how our work can help people enjoy the snow and avoid getting into trouble. The reports we get, from people in the public and private sectors, allow us to provide descriptions of individual accidents as well as look for trends in a larger group of events. There could be more new users in the 2020-2021 season and we’re looking for ways to help them learn about avalanche safety, while continuing to provide good information and education for more experienced users. Backcountry users in Colorado are diverse. There are a lot of them, they are in a lot of different places, they have a wide range of experience and education, and they are participating in a variety of activities. We hope we are providing a service that helps you. Please read the avalanche forecast before you go into the backcountry. Take the Friends of the CAIC’s Forecast Pledge and challenge your friends to do the same. Get out into the snow and when you get back, tell us what you saw. Most importantly, have a fun and safe 2020-2021 avalanche season.

References

American Avalanche Association, 2016 Snow, Weather, and Avalanches: Observation Guidelines for Avalanche Programs in the United States (3rd ed).

https://www.americanavalancheassociation.org/swag

Dreyfuss, S. E., and Dreyfuss, H.L. 1980. “A Five-Stage Model of the Mental Activities Involved in Directed Skill Acquisition” http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA084551&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf

Logan, S. L., and Greene, E. 2018. Forecast avalanche danger, avalanche activity, and avalanche accidents in Colorado, USA, winters 2014 to 2018. International Snow Science Workshop Proceedings 2018, Innsbruck, Austria. https://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item.php?id=2710

Maartensson, S., Wikberg, P, and Palmgren, P.. 2013. Swedish Skiers Knowledge, Experience and Attitudes Towards Off-Piste Skiing and Avalanches. International Snow Science Workshop Grenoble – Chamonix Mont-Blanc – October 07-11, 2013 https://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item.php?id=1822

McCammon, I. 2000. The Role of training in recreational avalanche accidents in the United States. Proceedings of the 2000 International Snow Science Workshop, October 1-6, Big Sky, Montana. https://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item.php?id=704

McCammon, I. 2002 . Evidence of Heuristic Traps in Recreational Avalanche Accidents. 2002 International Snow Science Workshop, Penticton, British Columbia. https://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item.php?id=837

National Institutes of Health. Competencies Proficiency Scale. https://hr.nih.gov/working-nih/competencies/competencies-proficiency-scale

Pronin, E. 2008. “How We See Ourselves and How We See Others”. Science. 320 (5880): 1177–1180.

Sapolsky, Robert M. 2017. Behave: the biology of humans at our best and worst. Penguin Books, New York.

St. Clair, A. 2019. Exploring the Effectiveness of Avalanche Risk Communication: A Qualitative Study of Avalanche Bulletin Use Among Backcountry Recreationists. MS thesis, Simon Fraser University.

Tase, J.. 2004 Influences on backcountry recreationists risk exposure to snow avalanche hazards. MA thesis, University of Montana

Zweifel, B., Techel, F., and Bjork, C. 2012. Who Is Involved In Avalanche Accidents? Proceedings, 2012 International Snow Science Workshop, Anchorage, Alaska https://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/item.php?id=1586