Late Sunday morning a backcountry snowboarder -- a Denver man and a long-time rider in the Berthoud Pass area -- and his dog were buried and killed in a sizable hard slab avalanche on the north side of Mines Peak, just northeast of the summit of Berthoud Pass. This was the first Colorado and US avalanche fatality of the season.

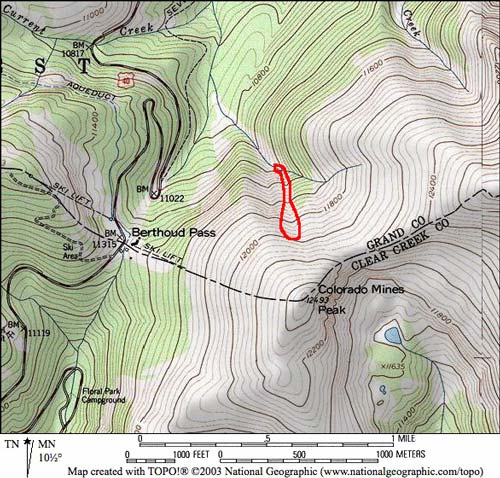

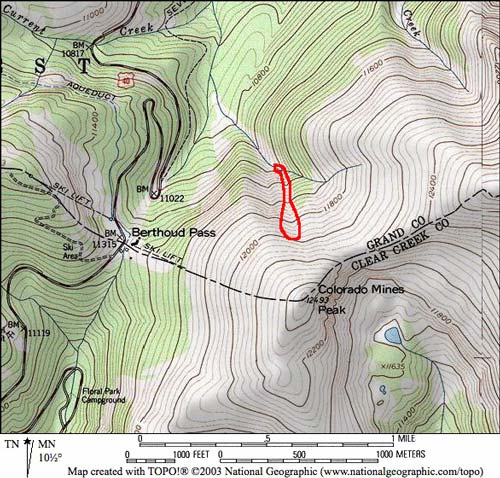

The avalanche,outlined in red,occurred in a path called Mines Peak 1. The hard slab avalanche fractured 400 feet across and fell 800 vertical feet.

Late Friday night a stronger than expected storm brought snow and strong winds to the Front Range. At Loveland Pass (11.5 miles to the south-southwest) both Arapahoe Basin and Loveland Basin ski areas reported 15 inches of new snow by early Sunday morning. All of this snow fell from late Friday night and during the day Saturday. Weather instruments on Loveland Pass recorded strong westerly winds averaging almost 20-30 mph with gusts into the 50s and 60s, and very similar snowfall and winds were reported on Berthoud Pass.

By Sunday morning skies had cleared but strong winds continued to cause blowing snow and loading of avalanche starting zones. (By mid afternoon Sunday several local backcountry skiers had spotted natural slab avalanches that released during the day.)

On Sunday morning three snowboarders set out from the summit of Berthoud Pass looking for powder. They climbed to the east and then traversed northward to the shallow bowl on the north side of Mines Peak (Mines Peak 1). Above treeline they stepped into their boards. The first rider cut under the big wind-roll of drifted snow and rode to the trees just above where the gully starts. The second rider tarted down, followed by his dog, and was in the middle of the slope when the snow shattered like a pane of glass. In an instant he was tumbled and swept away. The slide had broken out at the feet of the third rider. The time was about 10:30 AM. At this point the details become very incomplete. The rider at the top returned to the summit of Berthoud Pass to get help. The first rider started searching for his friend.

Looking down Mines Peak 1. The victim was last seen in the middle of the slope. The avalanche was 400 feet wide at the top of the slope but narrowed to 100 feet where it spilled into the gully. Debris filled the gully, but it was generally only about 10-15 feet across. (Photo Dale Atkins)

Skiers and snowboarders organized a response and set out to help, while rescuers from Grand County Search and Rescue and Alpine Rescue Team responded. Several small groups of locals raced to the slide, but in their haste one group triggered a second sizable release on the adjacent slope (Mines Peak 2), and for a long time Sunday there was a very real fear that as many as 2 or 3 more people had been buried in this second avalanche.

Mines Peak with the two triggered avalanches from Nov. 6, 2005. The fatal accident occurred in Mines Peak 1 (red). A second avalanche was triggered by others coming to help in Mines Peak 2 (yellow). No one was caught in this second avalanche. (Photo Dale Atkins)

Though the top several inches of snow was soft, underneath lurked a dangerous hard slab. The victim's friend rode down first without incident, but it was the victim who triggered the sizable hard slab (pencil hardness) avalanche in the avalanche path known as Mines Peak 1. The avalanche fractured from 1 to 3 feet (most of the slab was 1.5 feet thick) to the ground by 400 feet across, and released from an elevation of about 12,000 feet. It fell 800 vertical feet. The weak layer consisted of faceted (sugar-like) snow grains that formed after earlier October snows. The slope angle in this north-northeast facing starting zone measured 37 degrees. The avalanche ran a considerable distance and filled the lower gully with debris. The avalanche was classified as an HS-AR-R3D2-G.

Fracture line on Mines Peak 1. The depth in this spot is 2 feet. The top 4 inches is soft wind-affected snow. The middle 14 inches is very hard wind slab that was created by the weekend's new snow and strong winds. The bottom 6 inches is faceted sugar-like snow that first fell earlier in October. These grains had become loose and cohessionless. (Photo Dale Atkins)

Looking along the fracture line. Most of the fracture line was only about 1.5 feet deep, but did reach 3 feet in a few spots. The communication tower at the summit of Mines Peak is visible in the distance. (Photo Dale Atkins)

Apparently locals found the victim by spot probing near the toe of the debris just as organized rescuers arrived. The man had been buried for about 2 hours under 3-4 feet of snow. The victim had left behind -- either at home or in his car -- his transceiver. Efforts to resuscitate the victim failed, and Grand County Search and Rescue evacuated the body.

Rescuers from Alpine Rescue Team, Summit County Rescue Group, Flight for Life, and the Grand County and Clear Creek County Sheriffs' Offices assisted the rescue effort.

A steep slope, a weak layer of loose, faceted grains topped by a fresh wind slab only needed a trigger to set snow into motion. Tragically along came a group of riders looking for powder. In the simplest form it appears this accident was a case of powder lust, a dreaded malady that inflicts all of us who seek the steep and deep.

All the necessary ingredients for an avalanche were present and so too were the clues to the danger. The best clue were the strong winds and blowing snow that continued to load avalanche starting zones, even on Sunday morning. We have not yet spoken to the victim's friends, but we suspect that the hard snow conditions and earlier tracks may have caused false confidence.

A number of ski/rider tracks were on the east edge of the slide and we suspect those were put in late Saturday and maybe even a few on Sunday morning. Tracks are not a sign of stability and safety. Too often backcountry skiers and riders were just lucky that they did not hit the weakest zone of snow. A couple of other lessons learned deal with hard slabs and early season conditions.

Hard slab conditions on steep slopes should never be trusted. Recent weather conditions over the weekend -- strong winds -- were perfect for the formation of hard slabs.

Lastly, steep, high elevation northerly-facing slopes should never be trusted in the early season as it these slopes that will have the early-season weak layer. The dilemma is these same avalanche-prone slopes that have the snow and offer reasonable skiing and riding. The best advice we can offer is that we hope that you will use extra caution on these steep northerly aspects and be patient in your pursuit of powder. A small avalanche can ruin a whole more than just your day or season.

Atkins, Nov. 7, 2005

*}